Some 420 million years ago, during the late Silurian or early Devonian, the three sides of the Fire Triangle first came together. The first, an ignition source in the form of heat, had existed since the formation of the Universe itself. The second, atmospheric oxygen levels high enough to sustain combustion, emerged in the early Paleozoic, around 540 million years ago. The third, fuel, arrived when plants first colonised land. While we may never know precisely when or where the first fire ignited, we do know that it was literally the spark that changed the course of life on Earth.

Mythology is filled with stories that echo this paradox. Across cultures, numerous “Origin of Fire” myths tell of fire being stolen, and of the eternal price humanity must pay for its possession. Many recount how our control of fire unleashed consequences that revealed our mortality and lack of divine foresight - the inability to foresee the implications of our audacious acquisition. Indeed, the concept of Pandora’s Box has roots in an ancient pre-Socratic myth about fire. But is our fate truly sealed? Did the moment some long-extinct ancestor first mastered the fire triangle mark the beginning of the end - our slow, inevitable expulsion from a mythical Eden?

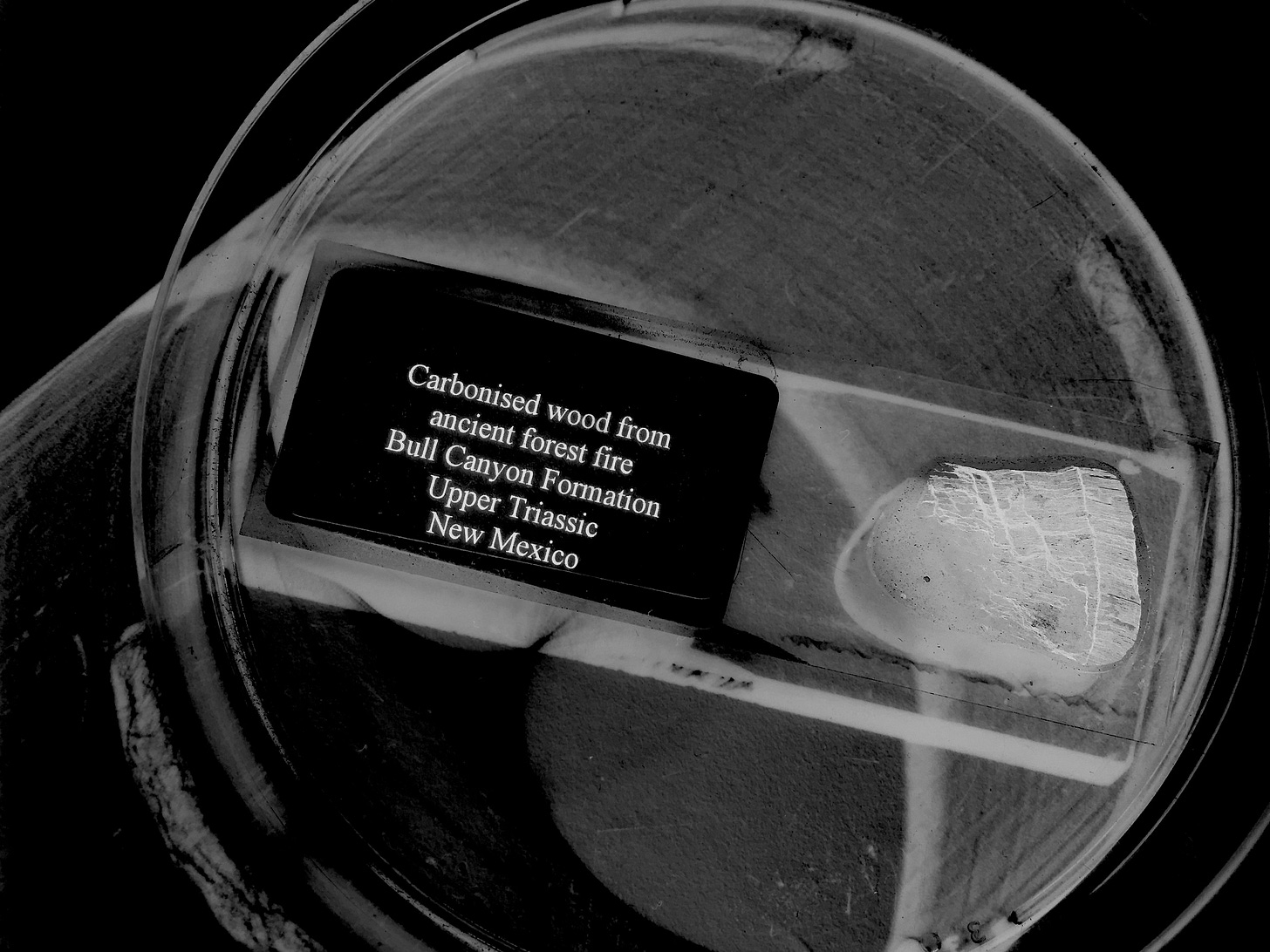

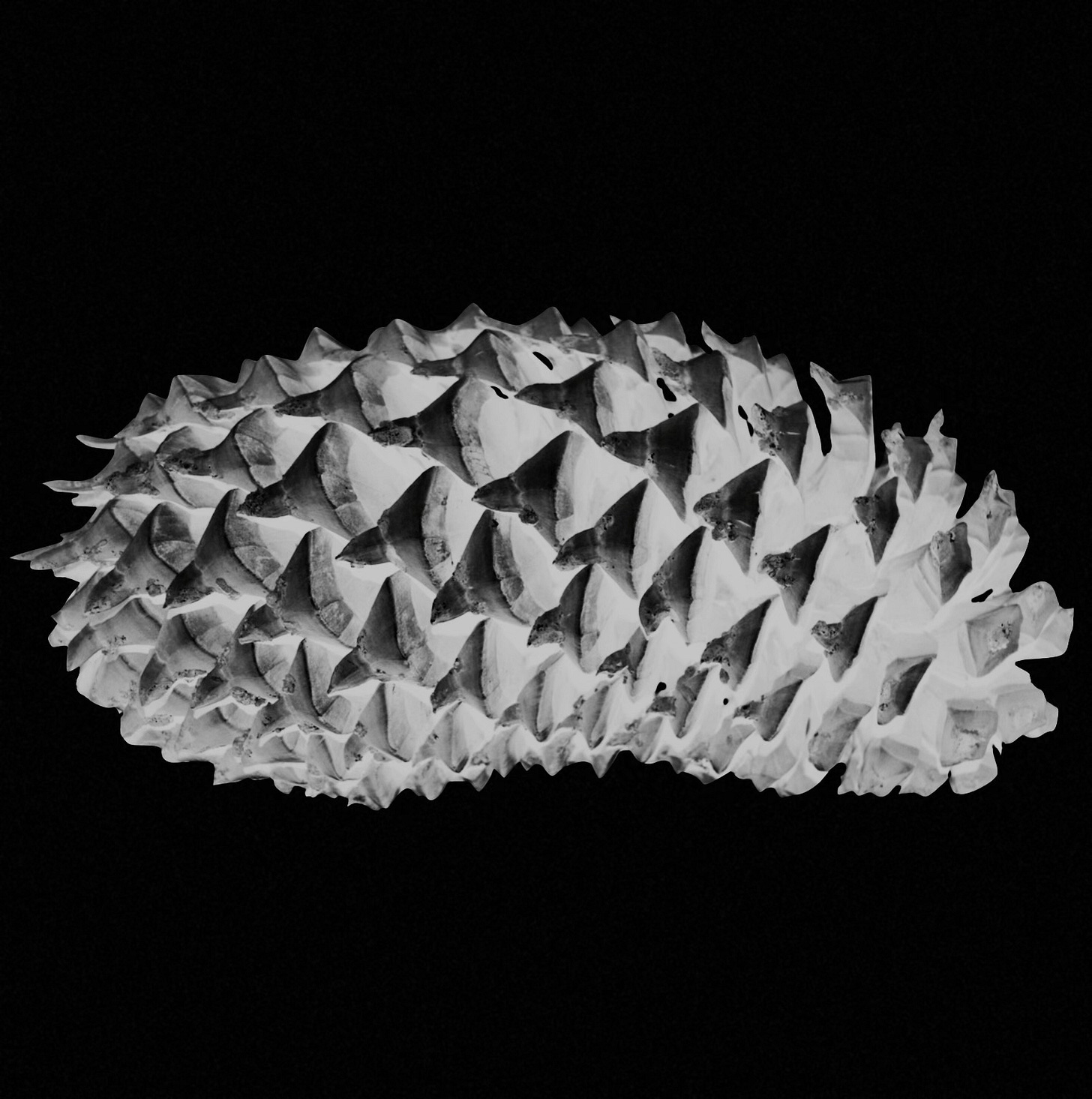

That is a question I have explored for many years. I first encountered fire ecology by accident in 1997, while visiting family in San Diego County, Southern California. During walks around their land, I collected an assortment of cones and seed-bearing specimens. Initially, I was drawn to their forms - the immense Coulter (below) and Digger pine cones, giants compared to those of pines native to the United Kingdom. My curiosity soon turned from their aesthetics to their function, particularly that of pyrophytes: species evolved to live with, and even depend upon, wildfire. Although I knew the region experienced wildfires, I had no idea it was among the most fire-prone in the United States, or that two of the fiercest modern wildfires would later sweep through that very landscape. When flames towering above treetops appeared on the evening news, my mother phoned her cousin. He told us the family had been evacuated, along with much of the nearby town, while he and a few neighbours stayed behind to help firefighters defend their homes.

Fire sits at the intersection of Earth’s systems and exerts influence far beyond the places where it burns. Recently, awareness of wildfire’s global impacts - especially on air quality - has grown. Yet this is only one of many ways fire shapes our planet. Earth remains the only known place in the Universe where the fire triangle is complete.

Without fire, our lineage would look very different. It shaped the landscapes in which our early primate ancestors evolved and, much later, our mastery of it underpinned the technologies that built not only our current civilisation but all that came before it. Ancient peoples revered fire, tending eternal flames in temples and worshipping fire deities.

Even today, fire retains its symbolic and emotional power. We find comfort in gathering around a hearth or campfire on a winter’s night. The global candle market, which was valued at roughly $14.2 billion in 2023 and projected to reach $23.4 billion by 2033, speaks to our enduring attraction to open flame. But, of course, in some other contexts, fire is framed not as friend, but as foe and a force not to be played with.

In the late 2000s, I began researching how cities might coexist with natural hazards - how nature might design a city. Initially, my scope was broad, encompassing earthquakes, eruptions, hurricanes, and even asteroid impacts. But the complexity of such systems demanded focus. When I began my PhD in 2010, my thoughts returned to those cones collected years before in the hills of San Diego, and to the wildfires that had since swept through them.

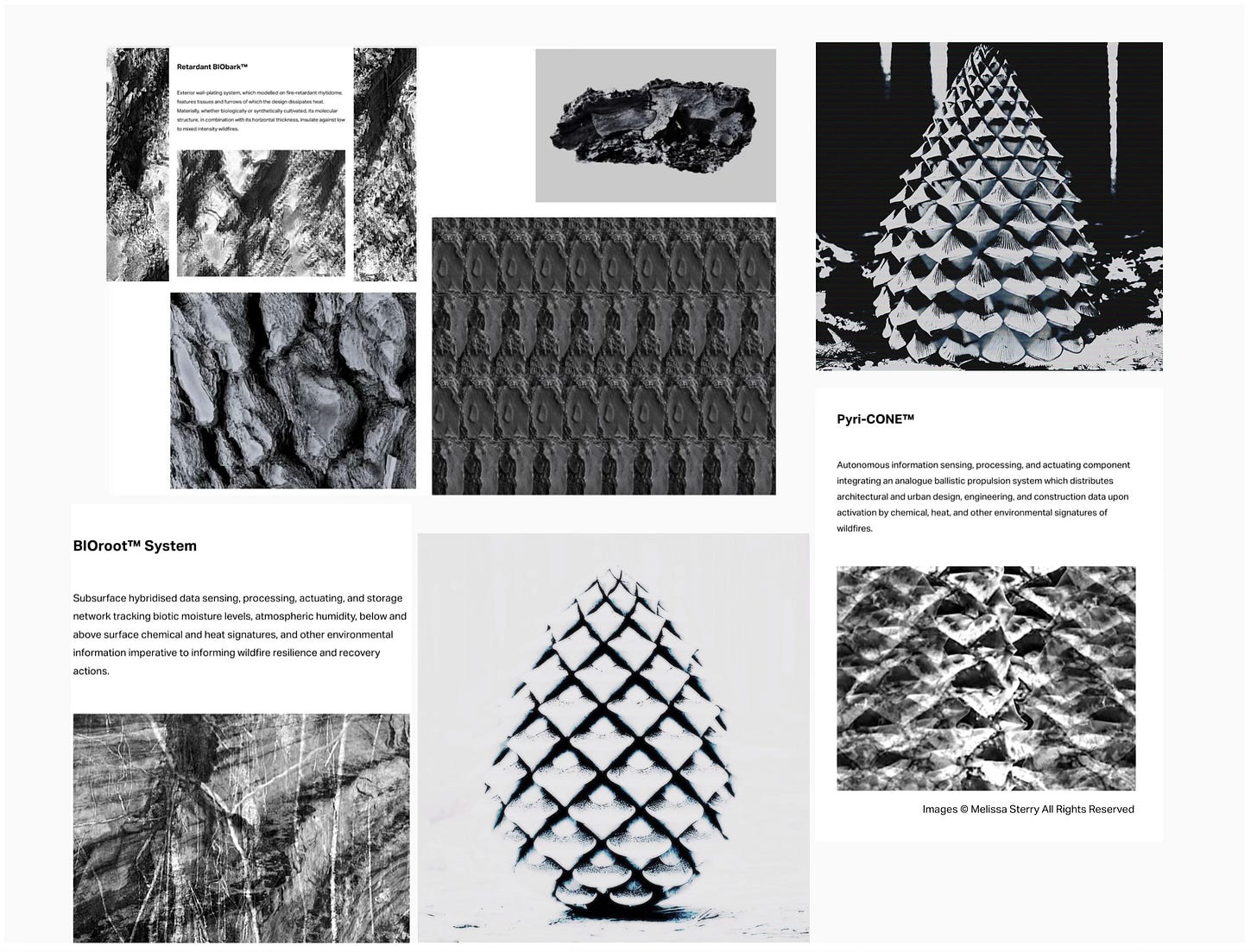

Panarchistic Architecture, and its subfield Pyrophytic Architecture™, are founded on the principle that even species evolved to withstand extreme natural forces have limits. Design cannot perform miracles, but it can integrate new knowledge to improve performance. And there is much new knowledge, both within and beyond fire ecology, for it to draw upon.

Working with nature, rather than against it, means recognising wildfire as an integral part of the reproductive cycle for pyrophytic species that depend upon it. Yet we cannot work with what we do not understand. The first step is not experimentation, but observation: learning how wildfires work. Their dynamics are complex, and so much so that we are still unravelling them. But each new insight brings us closer to coexisting, rather than simply surviving, in a world shaped by fire. Those that want to learn can find an outline of the science in the thesis chapter here.

Read more about Pyrophytic Architecture™ here.

Images: Research specimens, sketches, and other works by Melissa Sterry, 2017 - 2024.